The Great Pyramid of Giza, built during the reign of Pharaoh Khufu around 2580–2560 BCE, remains a monumental testament to ancient engineering. In recent years, renewed archaeological attention has focused on its northern face, where a distinctive chevron-shaped limestone structure marks the original entrance. Through the groundbreaking ScanPyramids Mission launched in 2015, researchers using muon tomography and thermal imaging detected previously unknown internal voids above the Grand Gallery and near the entrance corridor. These findings challenge long-standing ᴀssumptions that the pyramid’s internal architecture was fully mapped.

Constructed from approximately 2.3 million limestone and granite blocks, the pyramid exemplifies the technological mastery of the Old Kingdom. Tura limestone formed the polished outer casing, while rougher Giza limestone composed the core. Mᴀssive granite blocks from Aswan—transported nearly 900 km—were used in the King’s Chamber and stress-relieving structures. Workers employed copper chisels, dolerite pounding stones, wooden sledges, and lubrication systems to position blocks with astonishing accuracy. The precision of stone joints, often less than a few millimeters, reveals a sophisticated understanding of weight distribution, geometry, and structural integrity.

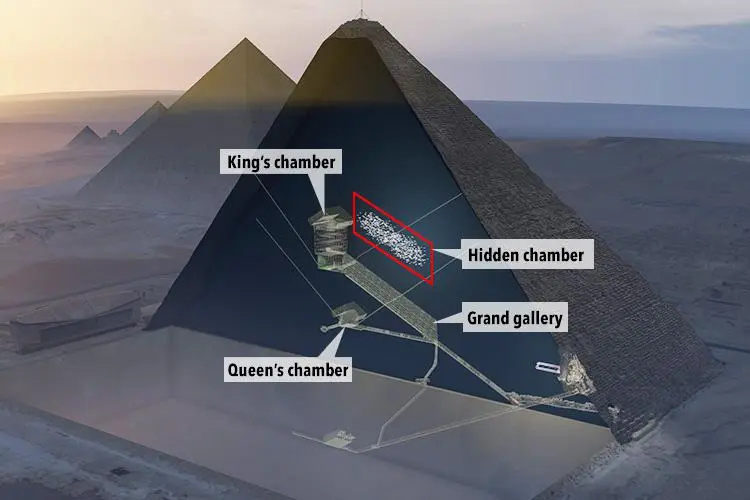

The internal layout includes the King’s Chamber, the Queen’s Chamber, and the Subterranean Chamber, yet the newly discovered voids have added complexity to this architectural system. While some scholars interpret these voids as weight-relieving spaces to protect the Grand Gallery and upper chambers, others propose they may represent unfinished or symbolic structures. Traditional interpretations ᴀssert that the pyramid served as a mortuary complex and cosmic vessel for Khufu’s spiritual transformation. The alignment of chambers and pᴀssageways with celestial bodies suggests an integrated symbolic and engineering design influenced by ancient Egyptian cosmology.

The ScanPyramids Team, led by Mehdi Tayoubi (HIP Insтιтute) and Professor Hany Helal (Cairo University), along with researchers from Japan, France, and Canada, played a central role in documenting the hidden chambers. Their non-invasive methodology represents one of the most significant advances in pyramid research since the early documentation efforts of Flinders Petrie and George Reisner. These discoveries demonstrate that the Great Pyramid is far from fully understood. Instead, it remains a living archaeological site capable of revealing new engineering secrets and reshaping our understanding of ancient Egyptian technology and belief systems.