The botched recovery and vandalism of Tutankhamun’s mummy (including its erection!) — and a connection to Downton Abbey.

Everyone ogles over the treasures of King Tut’s tomb — but few know how messy the recovery of the mummy was

Ancient Egypt’s most famous and recognizable pharaoh in the modern world was still a teenager when he died, and his nickname, King Tut, has become a household name.

When Howard Carter discovered and unsealed Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 and revealed its extraordinary contents, he sparked a global interest in archaeology and Ancient Egypt the likes of which had never before been seen.

It took his team eight years to catalog and remove all of the ancient artifacts within the relatively small tomb. One can only begin to imagine the wealth of relics entombed within the larger royal sepulchres surrounding Tutankhamun’s, prior to being plundered over the centuries.

New technologies and conservation continue to yield information about his treasures almost a century later.

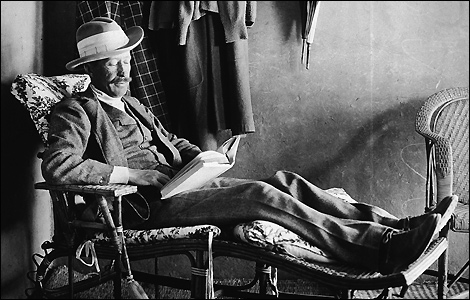

Carter (right) must have been dying of impatience while he awaited the arrival of Lord Carnarvon to begin excavating the tomb he found!

When Carnarvon Met Carter

George Herbert, the 5th Earl of Carnarvon, was the patron who footed the bill for the search for Tutankhamun’s tomb. He was also the lord of Highclere Castle, the impressive estate where Downton Abbey is filmed. And like the fictional Lord Grantham, Carnarvon married into money.

Is that Downton Abbey? Sort of — the show is set in the real-life Highclere Castle, once home to Lord Carnarvon, who paid for the search for and excavation of Tut’s tomb

He liked fast horses and even faster cars. A near-fatal automobile accident in 1903 (he was reportedly going a whopping 30 mph or so) left him in chronic pain, and his physician advised the restoring influence of a warmer climate. So he and Lady Carnarvon often spent their winters in Cairo, buying antiquities for their collection and sparking his pᴀssion for Egyptology.

Carnarvon only lived five months after being a part of the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun

In 1907, Lord Carnavon was introduced to a driven and stubborn young archaeologist named Howard Carter by French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero, who was the director general of the Egyptian Department of Antiquities.

From the very beginnings of their ᴀssociation, Carter wanted to excavate the Theban necropolis of the Valley of the Kings (modern-day Luxor) in search of the elusive tomb of a minor 18th Dynasty pharaoh, first known through a small faience cup inscribed with the king’s name that was found by American Egyptologist Theodore Davis in 1905.

Permission to excavate in the valley was granted to Carnarvon in 1914 but didn’t commence until 1917 due to World War I. After four relatively fruitless seasons, and with the final resting place of Tutankhamun undiscovered, Carnarvon was ready to put an end to Carter’s search. Were it not for Carter’s insistence to continue for one more season, the tomb might never have been found.

If Carver hadn’t insisted on searching for one more season, King Tut’s tomb might never have been found!

Was Tutankhamun murdered? Did he die from a chariot accident? We help solve one of the great mysteries of Ancient Egypt.

DISCOVER: How Did King Tut Die?

Talk about a 12-step program! These stairs were the first evidence of the wonders that lay within this untouched tomb

On the morning of November 1, 1922, the top of a sunken staircase was revealed. By the following afternoon, 12 steps had been cleared. Carter ordered his men to refill the staircase and sent off the now-famous telegram to Carnavon, who was in England at the time:

At last I have made wonderful discovery in Valley; a magnificent tomb with seals intact; re-covered same for your arrival; congratulations.

The earl’s death, five months after the tomb was opened, purportedly from a mosquito bite, is the stuff of legends and is regarded by some as evidence of the curse of the pharaoh.

Be careful, Carter and Co.! The poor mummy of King Tut was horribly mangled during its removal process

Off With His Head!

It wasn’t until 1925 that Tut’s mummy was finally revealed. The bands of linen cloth that covered the king from head to feet had been saturated by copious amounts of unguents and resins, leaving his desiccated skin the color and texture of nori seaweed. Perhaps it was thought that by making the boy king appear as Osiris, the god of the afterlife, the transgressions of his heretic father, Akhenaten, who foisted monotheism upon the unwilling population, would be forgiven.

Whoops! Carter and his team accidentally decapitated the Boy King when they took off the funerary mask

Over time these resins changed into a hardened black substance, acting as a glue and adhering his body to the coffin. Carter and his anatomist, Douglas Derry, had to chisel the king’s remains out in pieces. Tut’s mummy was unceremoniously decapitated by Carter and his team when its golden death mask was removed.

On the wall to the right, Tut is shown with his ka, or embodied soul, worshipping Osiris, the mummified god of the afterlife

The Osiris Connection: A Boner of Contention

Beneath their swaddling, Tutankhamun’s mortal remains had more than a few unusual features. According to Carter’s notes, a conical form, composed of linen bandages, was found atop the king’s head, its shape resembling the feathered, bowling pin-shaped atef crown of Osiris.

Also noted by Carter was that Tut’s mummy had a woody. The royal penis was embalmed and preserved in an upright nearly 90-degree angle, perhaps symbolically evoking Osiris’ fertility and regenerative powers.

PH๏τographed after unwrapping by Harry Burton, Tut’s member was reported missing in 1968, when British scientist Ronald Harrison took a series of X-rays of the mummy. His royal endowment sprung up on a CT scan in 2006, hidden in the sand surrounding the king’s remains.

The consensus among Egyptologists was that additional damage to Tutankhamun’s mummy was done by looters sometime after Carter had finished clearing the tomb of its contents in 1932 — most likely during World War II and again in 1968. Both ears were missing, and the eyes had been pushed in. The standing theory is that the looters had bribed the Valley of the Kings guards to let them in, steal the remaining jewelry left in the tomb, and “blinded” and “deafened” the mummy to keep it from coming after them.

The famous funerary mask of King Tut seems to help prove that Neferтιтi did indeed become pharaoh

A Recycled Mask From Neferтιтi

Interestingly, the most iconic of Tutankhamun’s treasures, his golden death mask, seems to have originally been intended for his stepmother, Neferтιтi.

The face, ears and beard of the beautifully wrought mask were modeled separately to represent the young king as Osiris. Research has revealed that one of the cartouche inscriptions found inside the mask was reinscribed in antiquity with Tutankhamun’s name imposed over the previous, partially erased cartouche of Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten, the official name used by Neferтιтi after she became co-pharaoh of Egypt. This has led some to believe that, like Hatshepsut, Ancient Egyptians attempted to edit out a woman’s rule as king.

Can you imagine how freaked out the museum staff must have been when they broke off King Tut’s funerary mask beard?!

The Broken Beard

In August 2014, the elongated braided beard attached to that iconic funerary mask accidentally snapped off while staff at the Egyptain Museum in Cairo were replacing a lightbulb in its glᴀss display case. A sloppy attempt to hastily reattach the beard with epoxy followed, further damaging the treasured 3,300-year-old mask. This iconic item was taken off display to be restored by a team of German specialists. The resinous glue was carefully removed and the beard reattached with beeswax, an adhesive used in antiquity.

This 1925 pH๏τo by Harry Burton shows that Tut’s beard had broken off previously

Interestingly, this wasn’t the first time the beard had been separated from the mask, though. PH๏τographs taken of the artifact in 1925 by Burton are of a beardless Tut, and it apparently wasn’t reattached until the 1940s.

The scarab on this necklace was created by a meteorite crash!

Jewelry That’s Literally Out of This World

Among the incredible objects discovered in Tut’s tomb was a protective scarab pendant featuring a rare chartreuse yellow gemstone originally identified as chalcedony by Carter. However, modern researchers determined that it’s not a stone at all but a type of extraterrestrial glᴀss created by a meteorite that crashed into the silica-rich sands of the Grand Sand Sea millions of years ago. Known as Libyan desert glᴀss, this material was valued by the Ancient Egyptians as having celestial origins. –Duke