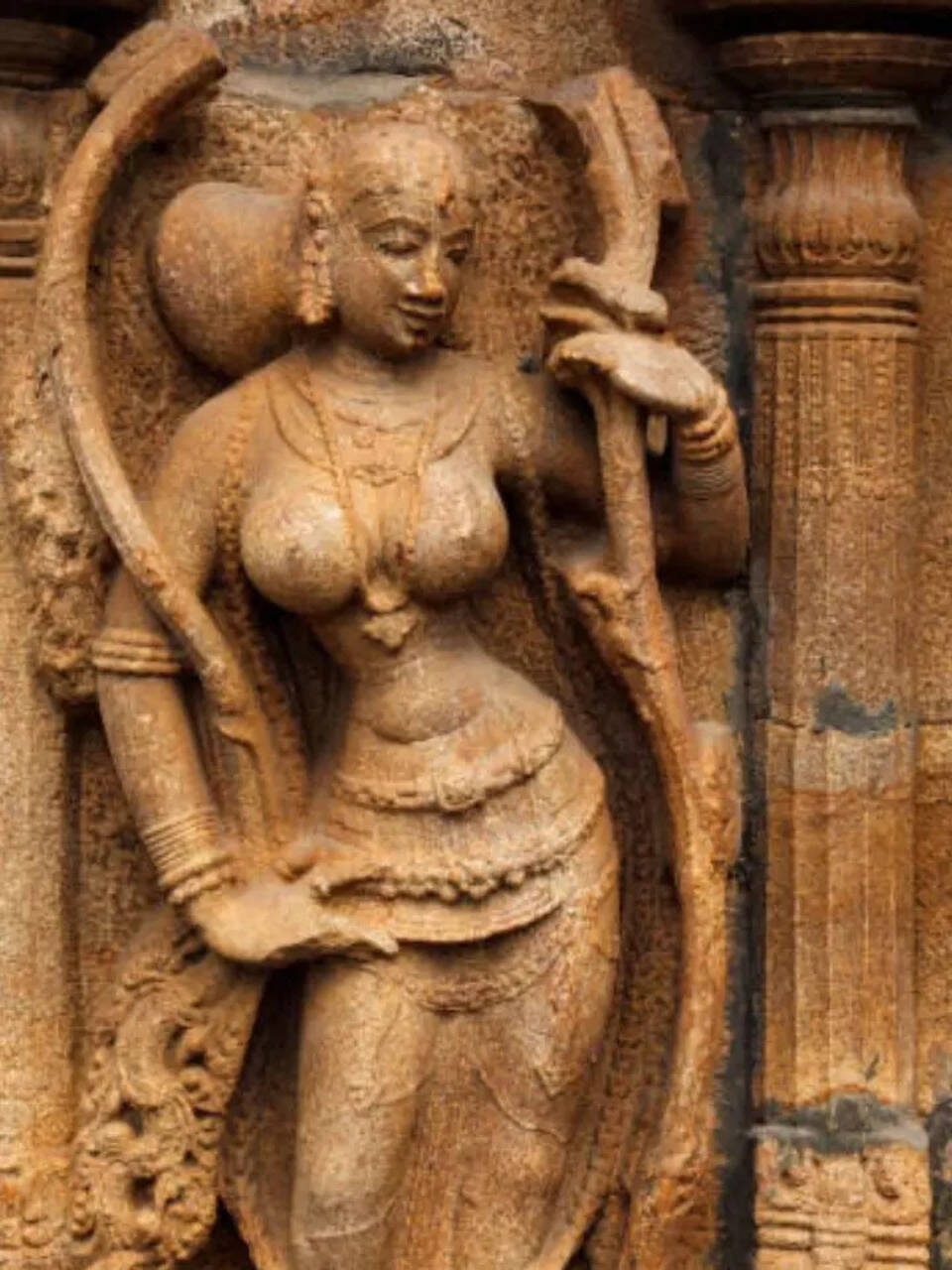

In the heart of India’s sacred architecture stand temples that are not merely places of worship but timeless libraries carved in stone. Among their intricate reliefs, hidden between depictions of gods, dancers, and cosmic battles, are figures that have puzzled modern observers for decades. These enigmatic carvings show two women holding objects that bear an uncanny resemblance to modern devices: one appears to hold a small, rectangular object to her ear as though speaking into a phone, while the other cradles a tablet-like slab in her hands, fingers poised as though writing or scrolling. At first glance, these figures seem like simple ornaments, yet the more carefully one looks, the more profound the questions become. Could it be possible that these ancient sculptors captured something far beyond their own time?

The sculptures are often attributed to temple art of the medieval period, dating from roughly the 9th to 12th centuries CE, during the golden era of Indian stone carving. These centuries witnessed the construction of monumental shrines like Khajuraho in Madhya Pradesh and Hoysaleswara in Karnataka, temples where artists sought to represent not only the divine but also the earthly experiences of daily life. To the trained eye of the art historian, the figures are part of a tradition of portraying attendants, musicians, and courtly women, complete with ornaments and ritual objects. Yet to the modern viewer, the resemblance of these hand-held objects to mobile phones and tablets is shocking. This collision of perception—between what scholars say and what our contemporary imagination interprets—creates fertile ground for speculation, myth-making, and mystery.

One hypothesis often presented by archaeologists is that the “phone” is actually a simple mirror, an object commonly depicted in the hands of women in temple sculpture, symbolizing beauty, self-awareness, and the eternal cycle of life. The “tablet,” meanwhile, could represent a stylus and palm-leaf manuscript, a conventional motif denoting learning and wisdom in ancient Indian culture. Such interpretations align seamlessly with the traditions of the time and offer rational, historically consistent explanations. And yet, despite the plausibility of these academic views, the modern mind continues to struggle with the resemblance. How is it that a piece of stone carved a millennium ago should so precisely echo the technological instruments that dominate our own daily lives?

Here lies the paradox: symbols of antiquity begin to look like artifacts of modernity. For some, this is mere coincidence—a case of the human mind searching for patterns, a phenomenon psychologists call pareidolia, where we interpret ambiguous images in familiar ways. For others, however, the uncanny likeness is not accidental but rather evidence of a hidden narrative in human history. Alternative researchers, often dismissed by mainstream academia, suggest that such imagery might reflect contact with advanced civilizations now lost to time, or even with knowledge that transcended eras, carried by myth, oral tradition, or perhaps something far stranger.

The fascination with these sculptures grows from this tension between the rational and the mysterious. Throughout history, human beings have left behind symbols that future generations reinterpret according to their own cultural lenses. Just as medieval Europeans might have seen visions of saints in celestial phenomena, we see echoes of our own age in the carvings of the past. And yet, there remains something unnervingly precise about these figures: the hand raised to the ear in the exact gesture of a phone call, the downward gaze of concentration that so closely mirrors the posture of a modern person absorbed in a digital screen. Such details seem less like accidents of artistic convention and more like moments of prophecy carved into stone.

What if these sculptures are not merely mirrors and manuscripts but something more? Could they represent the persistence of archetypes—universal images that recur across time, as the psychologist Carl Jung once proposed? Or might they suggest that technological forms are not purely products of linear progress but patterns that emerge cyclically in human culture, discovered, forgotten, and rediscovered across ages? If so, then the woman with her “phone” and her companion with the “tablet” may be more than just artistic flourishes: they could be silent witnesses to a deeper truth, one that challenges our understanding of human development and the continuity of knowledge.

There is also the possibility of metaphor. Ancient artists often encoded philosophical and spiritual meanings into their work, using physical objects as symbols of abstract truths. A mirror might signify self-reflection, while a manuscript might symbolize the transmission of wisdom. If the modern world sees them as a phone and a tablet, perhaps this too is telling: we have so entwined our lives with technology that we interpret ancient art through the lens of our devices. In this sense, the sculptures act as a cultural Rorschach test, reflecting not just the intentions of their creators but also the obsessions of their viewers a thousand years later.

Yet one cannot easily dismiss the allure of the “forbidden” interpretation: that somehow, these sculptures hint at knowledge beyond their age. Throughout history, there have been legends of lost civilizations—Atlantis, Lemuria, or vanished empires whose wisdom was said to surpᴀss that of their successors. Could the artisans of medieval India have inherited fragments of such knowledge, consciously or unconsciously embedding them in their stonework? Could they have glimpsed, through vision or dream, the shapes of tools yet to be invented, encoding them into their sacred walls as cryptic messages for the future? Such questions border on the fantastic, yet they persist precisely because they speak to our deepest curiosity: the longing to believe that history holds mysteries yet unsolved.

Ultimately, the enigmatic sculptures remind us of the layered nature of human heritage. Whether we see in them mirrors and manuscripts or phones and tablets, they compel us to question not only the past but also ourselves. They are artifacts of ambiguity, poised delicately between art and prophecy, between the certainties of scholarship and the seductions of mystery. Perhaps the true power of these carvings is not that they depict advanced technology or foreshadow our digital age, but that they invite us to wonder, to imagine, and to confront the possibility that the boundaries we draw between past, present, and future are not as fixed as we believe.

In the end, the silent figures carved into stone are less interested in providing answers than in provoking questions. They stand in their quiet alcoves, weathered by centuries, gazing down upon generations who have come and gone, their meanings shifting with each age. To the people of their time, they were sacred symbols; to us, they are enigmas. And perhaps that is the most enduring lesson of all: that history is not a closed book but an open dialogue between the living and the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ, between the known and the unknown, between the certainty of what is written and the mystery of what remains unsaid. Looking at these sculptures, one cannot help but ask: did they know something we have forgotten, or are we merely seeing ourselves reflected in their eternal stone gaze?