A monument on the cliffs of Persia

High on a limestone cliff in western Iran, towering 100 meters above the ground, lies one of the most extraordinary monuments of the ancient world: the Behistun Inscription. Commissioned around 522 BCE by Darius I, the great king of the Achaemenid Empire, this monumental relief and multilingual inscription combine art, politics, and propaganda. To the casual eye, it is a mᴀssive carving of figures, cuneiform text, and divine symbols. To historians and linguists, it is nothing less than the key to unlocking cuneiform writing, just as the Rosetta Stone unlocked Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The historical context: Darius and empire

The Achaemenid Empire, founded by Cyrus the Great, stretched from Anatolia and Egypt to India. When Darius seized the throne in 522 BCE, he faced immediate turmoil: rebellions erupted across the empire. To secure his authority, he turned not only to military force but also to monumental propaganda. The Behistun Inscription was his declaration to the world, carved permanently into stone, visible from miles away, and proclaiming both his victories and his divine legitimacy.

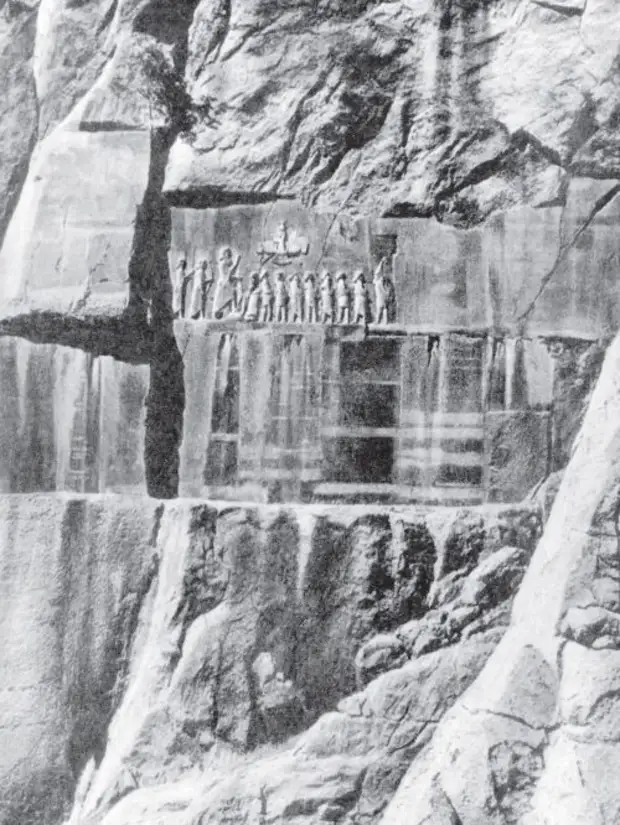

The relief: art as power

The central relief depicts Darius I standing tall, his arm raised in authority. Before him kneel or stand nine bound captives—leaders of rebellions he defeated. Above Darius hovers the winged symbol of Ahura Mazda, the supreme god of Zoroastrianism, affirming divine support. The composition is clear: Darius is the rightful king, chosen by the gods, victorious over pretenders. The image is propaganda in stone, an eternal reminder of his power.

The text: three languages, one message

Beneath and around the relief stretch over 1,200 lines of cuneiform text, written in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian (a dialect of Akkadian). This trilingual approach mirrored the empire’s vast diversity and ensured the message could be read across regions. The content is both narrative and political: Darius recounts his lineage, his ascension to the throne, and the suppression of rebellions. He denounces his rivals as liars who falsely claimed kingship, branding them as deceivers against both man and god.

The Rosetta Stone of Mesopotamia

For centuries, cuneiform was a lost script. When modern scholars rediscovered the Behistun Inscription in the 19th century, it became the breakthrough that allowed cuneiform to be deciphered. British officer Henry Rawlinson, in the 1830s, risked his life climbing the sheer cliff to copy the inscriptions. Comparing the known Old Persian text with the Elamite and Babylonian versions, scholars gradually unlocked the secrets of Mesopotamian languages. Just as the Rosetta Stone enabled the reading of Egyptian hieroglyphs, Behistun became the Rosetta Stone of cuneiform.

The peril of study

The pH๏τo of early 20th-century scholars clinging to ladders against the sheer cliff captures the danger of studying Behistun. For decades, researchers risked falls and death to copy and analyze the inscriptions. Only with modern technology has it become possible to study the monument safely, using drones and digital imaging. Yet those perilous climbs symbolize the dedication of scholars to preserving humanity’s earliest voices.

Propaganda and legitimacy

The Behistun Inscription was not neutral history. It was political propaganda. By portraying his enemies as “liars” and emphasizing his divine mandate, Darius crafted a narrative of legitimacy. This propaganda was effective in uniting the empire, reminding subjects that rebellion was both futile and sinful. But to modern historians, the text also reveals the complexity of empire: the struggles of succession, the diversity of peoples, and the fragile balance of power.

Zoroastrian echoes

The invocation of Ahura Mazda in the relief is one of the earliest royal references to Zoroastrian belief. It shows how religion and state were intertwined in Persian kingship. By placing himself under the winged god, Darius claimed not just political but spiritual authority. This intertwining of religion and rule would echo through later empires, influencing political theology for centuries.

Legacy and modern recognition

In 2006, the Behistun Inscription was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognized for its unparalleled historical significance. Today, it remains one of the most important archaeological monuments in the Near East. For Iranians, it is part of a cultural legacy reaching back 2,500 years. For the world, it is a testament to the power of writing, the resilience of language, and the ingenuity of modern scholarship.

Conclusion: a voice across millennia

The Behistun Inscription is more than stone and text. It is a voice from 2,500 years ago, speaking across time. It proclaims the ambitions of kings, the struggles of empires, and the interplay of religion and politics. But it also serves as a bridge between ancient and modern, enabling us to hear the words of Mesopotamia after millennia of silence. As long as the cliffs of Behistun stand, Darius’s voice—and the languages of the ancient Near East—will not be forgotten.