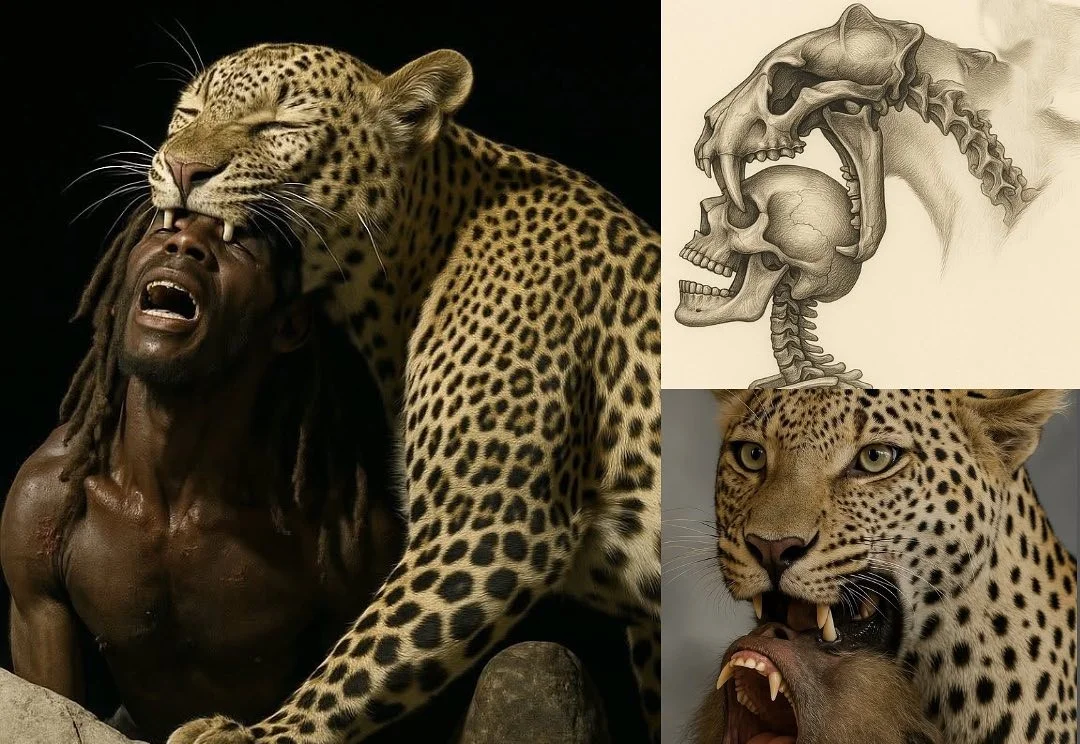

A groundbreaking discovery in Tanzania’s Olduvai Gorge has sent shockwaves through the scientific community, reshaping our understanding of early human history. On May 29, 2025, researchers unveiled a 1.8-million-year-old Homo habilis skull bearing chilling puncture marks—evidence of a lethal attack by a large feline, likely a leopard. This fossil, one of the oldest signs of predation on humans, paints a haunting picture of our ancestors as prey, not predators, in the perilous African savanna. Far from the dominant species we envision, early humans lived in constant fear of ambush. What does this find tell us about our evolutionary journey from hunted to hunter? Let’s explore this fossil’s story, its implications for human survival, and the profound legacy it leaves behind.

Olduvai Gorge, a cradle of human evolution, has yielded countless fossils, but none as evocative as this Homo habilis skull, discovered in 2024 and detailed in a Nature study on May 29, 2025. Homo habilis, dubbed “handy man” for its tool-making skills, lived 2.4 to 1.4 million years ago, bridging australopithecines and later Homo species. This skull, dated to 1.8 million years via potᴀssium-argon methods, per Smithsonian Magazine, bears two distinct puncture marks on the cranium. Analysis by paleontologists at the Max Planck Insтιтute, using 3D imaging and comparative bite patterns, confirms these match the canines of a Panthera pardus (leopard), a predator common in Pleistocene Africa, per National Geographic. This find not only rewrites Homo habilis’ ecological role but also illuminates the brutal survival challenges our ancestors faced.

The Fossil Evidence: A Leopard’s Lethal Strike

The skull’s puncture marks, spaced 3.5 cm apart, align with a leopard’s bite force of 300-400 pounds per square inch, capable of crushing bone, per Science Advances. Micro-CT scans revealed microfractures radiating from the holes, suggesting a swift, powerful bite to the head, likely a surprise attack, per Nature. Leopards, known for ambushing prey and dragging carcᴀsses into trees, were formidable threats in the open savanna, per The Guardian. The fossil, likely from an adult male Homo habilis (based on cranial sutures), shows no signs of healing, indicating a fatal attack. This contrasts with earlier finds, like a 1.5-million-year-old Homo erectus femur with healed bite marks, suggesting survival, per ScienceDaily. The Homo habilis fossil’s pristine condition, preserved in volcanic ash, offers a rare snapsH๏τ of predation, per @PaleoNewsX.

Life as Prey: Homo Habilis’ Precarious Existence

Homo habilis, standing 4 feet tall with a 510cc brain, was no match for leopards, which weighed up to 200 pounds and could leap 20 feet, per National Geographic. Unlike later Homo species, Homo habilis lacked advanced weapons, relying on crude stone tools (Oldowan technology) for scavenging, not hunting large prey, per Smithsonian. Their diet—60% plants, 30% small animals, per isotopic analysis—left them vulnerable in open landscapes, per Journal of Human Evolution. The savanna’s food web, with predators like lions, saber-toothed cats, and leopards, placed Homo habilis low in the food chain, per The Guardian. Social groups of 10-20 offered some protection, but nighttime ambushes, as suggested by the skull’s context, were ᴅᴇᴀᴅly, per Nature News. X posts from @FossilFanatic emphasize the “constant fear” narrative, noting leopards’ nocturnal hunting patterns likely exploited Homo habilis’ poor night vision.

Evolutionary Implications: From Hunted to Hunter

This fossil underscores humanity’s transformation from prey to predator, a journey spanning millions of years. By 1.5 million years ago, Homo erectus developed Acheulean tools and hunted antelope, per Science Advances. Brain size grew to 900cc, enabling cooperative hunting and fire use by 400,000 years ago, per Smithsonian. These adaptations shifted humans up the food chain, reducing predation risk. The Homo habilis skull, however, captures a humbler origin, highlighting resilience despite vulnerability, per National Geographic. Evolutionary biologist Mary Leakey, who pioneered Olduvai research, noted such fossils reveal “survival against odds,” per Leakey Foundation archives. The find challenges romanticized views of early humans as dominant, showing a species shaped by fear and adaptation, per @SciDailyX.

Broader Significance: Rewriting Human History

The discovery redefines Homo habilis’ ecological niche, suggesting predation pressure drove tool innovation and sociality, per Nature. Compared to other finds—like a 3.3-million-year-old Australopithecus skull with crocodile bite marks, per Science—it’s among the earliest evidence of hominin predation. Its preservation, aided by Olduvai’s alkaline soils, makes it a paleontological gem, per Smithsonian. Public reaction on X is awestruck, with @AnthroGeekX calling it “a window into our fragile past,” though some, like @SkepticPaleo, debate if the marks could stem from scavenging, not predation. The fossil’s display at Tanzania’s National Museum, announced May 2025, aims to educate on human vulnerability, per UNESCO. It also sparks questions about modern human-animal conflicts, as leopards still inhabit East Africa, per The Guardian.

The 1.8-million-year-old Homo habilis fossil from Olduvai Gorge is more than a relic—it’s a testament to humanity’s fragile beginnings. Marked by a leopard’s ᴅᴇᴀᴅly bite, it reveals our ancestors as prey, living in fear on the African savanna. This find not only deepens our understanding of Homo habilis but also celebrates the evolutionary triumph that turned hunted into hunters. As we reflect on this chilling discovery, what other secrets lie buried in Olduvai?