The Currency of Kindness: What a Woodshop, a Dog, and a $2,400 Ramp Taught Me About True Value

Part I: The Silence of the Sawdust

Ten years ago, the silence hit harder than any hammer. The Superintendent stood in the middle of my classroom, the place I had called Woodshop for three decades, and called my life’s work “obsolete.” He said the future was digital, not sawdust. He never saw a juvenile delinquent cry into the matted fur of a dying Golden Retriever.

The district voted to turn my Woodshop into an “Innovation Lab.” They sold the heavy lathes for scrap metal and replaced my sturdy, honest oak workbenches with flimsy plastic tables and glowing tablets. “Frank,” they told me, “kids don’t need to know how to build things. They need to know how to code things.”

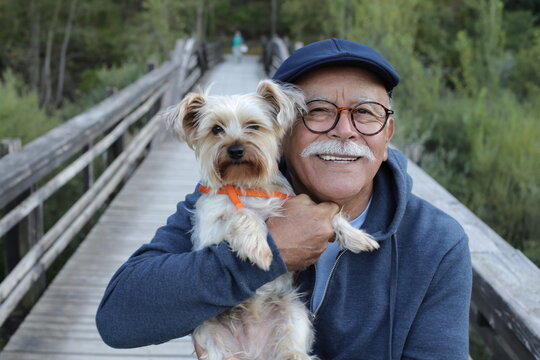

I didn’t argue. I just looked down at Barnaby, my twelve-year-old Golden, who was sleeping in his usual corner on a fragrant pile of pine shavings. Barnaby was the real teacher in that room. I was just the guy who unlocked the door.

For thirty years, I taught the boys who didn’t fit in the standard grid: the angry ones, the quiet ones, the ones whose energy made algebra impossible but who could sand a piece of maple until it felt like silk. My job wasn’t just carpentry; it was triage.

Part II: The Anger and the Anchor

Then there was Tyler. He came to me in his sophomore year, a walking knot of teenage rage. Father gone, Mom working two brutal shifts. His suspension record was a declaration of war on the world. He walked into Woodshop with his hoodie cinched tight, his fists jammed deep in his pockets, daring me to challenge him.

I didn’t. I just pointed to the raw woodpile.

For the first month, Tyler’s work was purely destructive. He sawed with rage. He hammered like he was trying to hurt the nails. Most teachers would have sent him to the office for the chaos he created.

But I had Barnaby.

One rainy Tuesday, Tyler messed up a crucial cut on a nightstand. The error was minor, but it triggered something primal. He threw his safety goggles across the room and collapsed against the wall, his head buried in his hands. He was shaking, not with cold, but with bottled-up fury.

Barnaby, whose arthritic hips made walking an ordeal, got up. Click, click, click went his claws on the concrete floor. He limped the agonizing distance to Tyler and shoved his big, gray-muzzled head right under the boy’s arm, resting his heavy chin against Tyler’s ribcage.

Tyler froze. And then, I saw it: the tight, white-knuckled fist loosened. The fingers uncurled slowly and buried themselves in Barnaby’s golden, slightly damp fur. The shaking stopped.

“He’s old,” Tyler whispered, his voice cracking. It was the first time he’d spoken to me without a defensive sneer.

“Yeah,” I said, not looking up from my paperwork. “He’s got bad days and good days. Don’t we all.”

Part III: The $2,400 Ramp

A few weeks later, I assigned the Final Project. “Build something that matters,” I told the class. “Don’t build it for a grade. Build it for someone you care about.”

Most kids built competent spice racks or baseball bat displays. Tyler, however, stayed late every single day. He stopped wearing the hood. He started measuring twice, cutting once. He treated the grain of the oak with a reverence I hadn’t seen since my own apprenticeship.

On presentation day, Tyler unveiled his project. It wasn’t furniture. It was a ramp—carpeted, sturdy, with gentle slopes and reinforced railings.

“Who’s that for, Tyler? Your grandma?” a wise guy in the back jeered.

Tyler ignored him. He walked over to the corner, gently woke up Barnaby, and carefully guided the old dog to his ramp. Tyler had noticed that Barnaby couldn’t climb the two steps into my small office anymore. He’d seen the dog wince when stepping up to his bed.

Barnaby walked the ramp, tail wagging slowly, and curled up on his pine shavings.

Tyler looked at me, his eyes wet but clear. “He shouldn’t have to hurt just to get to his bed, Mr. Frank.”

That was the last year of Shop Class. The tech overhaul arrived that summer. I took early retirement. Tyler graduated and vanished into the world. Barnaby passed away peacefully on my back porch that autumn.

Part IV: The Obsolete Man and the Restoration

Fast forward to this morning. I was standing in my driveway, hammering a rusty “For Sale” sign into the lawn. The pension wasn’t keeping up. The house was too big, and the arthritis in my hands was getting worse. I felt like a relic. Obsolete.

Suddenly, a massive, gleaming black pickup truck pulled up to the curb. On the side, in bold, honest letters: “T.J. Custom Construction & Restoration.”

A man stepped out. Broad shoulders, hands calloused by real work, a face weathered by sun and wind. He strode up to me, grabbed the “For Sale” sign, yanked it out of the ground, and threw it into the back of his truck.

“Tyler?” I squinted.

“Put the hammer away, Mr. Frank,” he smiled, a smile that crinkled the corners of his eyes. “You aren’t selling.”

“Tyler, I can’t keep up with the repairs,” I stammered. “And the taxes…”

“I bought the lien,” he said simply. “And my crew is coming next week to fix the roof and the porch. On the house.”

I was stunned. “Why, son? Why would you do this?”

He whistled. From the passenger side of the truck, a Golden Retriever puppy tumbled out, tripping over its own oversized paws, a joyous, golden menace.

“This is Barnaby the Second,” Tyler grinned. “He’s a menace. He needs to learn how to sit still and mind his manners.”

Tyler looked at my empty garage, then back at me. “And I need to hire some apprentices. But these kids today… they know how to swipe a screen, but they don’t know how to read a tape measure. They don’t know that if you rush the sanding, the stain won’t take.”

He put a heavy, familiar hand on my shoulder. “I’m reopening the shop, Mr. Frank. In your garage. Saturday mornings. I provide the wood. You provide the wisdom.”

I looked at the puppy chewing on my shoelace. I looked at the man who used to be a broken boy, now standing before me as a successful man.

“They told us we were obsolete, Tyler,” I whispered, the thickness in my throat returning.

“They were wrong,” Tyler said, looking down the street where the new ‘Innovation Lab’ stood. “We build the world they live in.”

The Final Lesson

We live in an age of artificial intelligence, automated checkouts, and digital everything. We are obsessed with faster, cheaper, and newer. We’ve been told that tangible skills are irrelevant.

But you cannot automate the feeling of a job well done. You cannot download the peace that comes from working a raw piece of oak into something beautiful. And you certainly cannot code the unconditional love of a dog saving a boy’s life.

If you have a child who struggles in a sterile classroom, put a hammer in their hand. Give them a task, not a tablet. Give them the chance to build something real.

Because the world doesn’t just need more software. It needs more builders. It needs more healers. It needs more Tylers.

Long live Shop Class.